This data plot shows infrared observations by NASAs Spitzer Space Telescope of a system of seven planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1, an ultra-cool dwarf star. With its primary mission long completed, and some of its instruments no longer operational, it is still functional as an exoplanet observer. The Spitzer space telescope is another space-based observatory that was originally launched as an infrared observatory. Kepler has discovered thousands of exoplanets, including many hot Jupiter and Neptune-sized planets, and a good number of Earth-sized planets.

#MAKE STAR CHARTS WITH STARRY NIGHT PRO PLUS 7 PATCH#

They detect and characterize exoplanets, especially Earth-like ones, by using Transit Photometry continuously on a single small patch of sky. To overcome this, observatories such as the Kepler Space Telescope are launched into orbit. If a star is being examined using a ground-based telescope, daytime prevents continuous measurements, and atmospheric interference (i.e., twinkling) adds noise to the light curve, limiting the sensitivity and preventing the detection of small planets.

Small, Earth-sized planets produce tiny dips in light intensity. Many stars exhibit inherent variability in their brightness, too, but the exoplanet transit dips are usually brief by comparison. The graphs of starlight versus time, known as light curves, can be complex if multiple planets are transiting – each with a different dip amount, duration, and interval – all summed together. This data plot shows infrared observations by NASAs Spitzer Space Telescope of a system of seven planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1, an ultracool dwarf star. By recording the brightness of the starlight continuously over a long period of time, we can determine the length of a planet’s year and the radius of its orbit. The dip re-occurs every time the planet completes an orbit. The amount of the reduction is proportional to the size of the planet. Fortunately, that’s still a lot of stars! On a regular interval each planet transits the disk of its star, temporarily causing a slight reduction of the star’s light (on the order of 1 part in 10,000) as viewed from Earth. Transit methods only work for the small percentage of star systems that are oriented edge-on towards Earth. The TRAPPIST-1 discovery used the transit method. Radial Velocity and Stellar Astrometry are other methods that detect the subtle motions of stars caused by orbiting planets tugging on them gravitationally. measuring the dimming of a star’s light when its planets pass between us and the star. The most fruitful of these techniques has been Transit Photometry

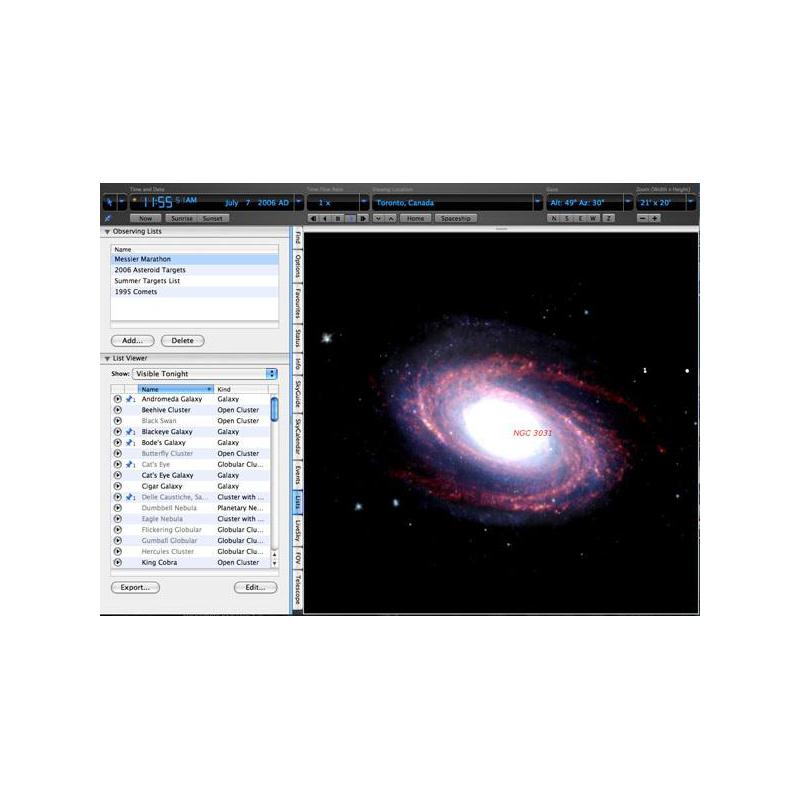

By far, the easiest methods involve measuring the small effects that the planets have on their star. So we have to rely on indirect methods to detect and characterize them. Image created with Starry Night Software.Īpart from a few special exceptions, directly observing planets hidden in the glare of their stars is beyond our current technology.

TRAPPIST-1d in transit across the disc of the TRAPPIST-1 star. While a great many Earth-sized extra-solar planets (exoplanets, for short) have already been catalogued, this discovery brings us another step closer to answering one of the big questions in the universe. Further surveys however, will be conducted in the future. Our own SETI (the Search for Extra- terrestrial Intelligence) has monitored the TRAPPIST-1 system for any artificial radio signals but so far has not detected any alien transmissions. Our broadcasts of Happy Days, Three’s Company, and Charlie’s Angels are arriving there now. If advanced intelligent life has evolved in the TRAPPIST-1 system, they could already have detected our radio and television transmissions. The TRAPPIST-1 planets were the exception, they were assigned letters in order of distance after subsequent planets were discovered. Progressive lowercase letters are used (c, d, e and so on) when more than one planet is found in a system, with the letters assigned in order of discovery, not distance from the star. Video created with Starry Night Software.Īn exoplanet is named after the star it orbits, followed by a lowercase letter (starting with "b". A fly-by of the TRAPPIST-1 system planets.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)